It's Spring Break, and I’ve gone back to the old drawing table. Literally. I was inspired to clear the space of books and dust while reading a book about Calvin and Hobbes’ creator Bill Watterson. Reading about his influences, Charles Schultz, Walt Kelly and George Herriman I had a flashback to my time as an art student at Eastern Kentucky University. It was in a couple of those classrooms that I learned that despite a lifelong fascination and appreciation for art, everything that I thought was art, was actually something else. Here I was introduced to concepts like “kitsch” and “lowbrow”. All of Stan Lee’s creations, for example, were considered “juvenile fantasy”.

This bothered me quite a bit, and I couldn’t explain or really understand why. Almost without fail, students would be asked who their influences were, and mine were often deemed “not artists”. Why was that? It certainly wasn’t because they lacked a certain set of skills. Maybe it was the way they chose to exercise them? Perhaps it had to do with the audience for whom they utilized those skills? I’m still not quite sure. I’m fairly certain that concepts of culture and class enter the equation, though.

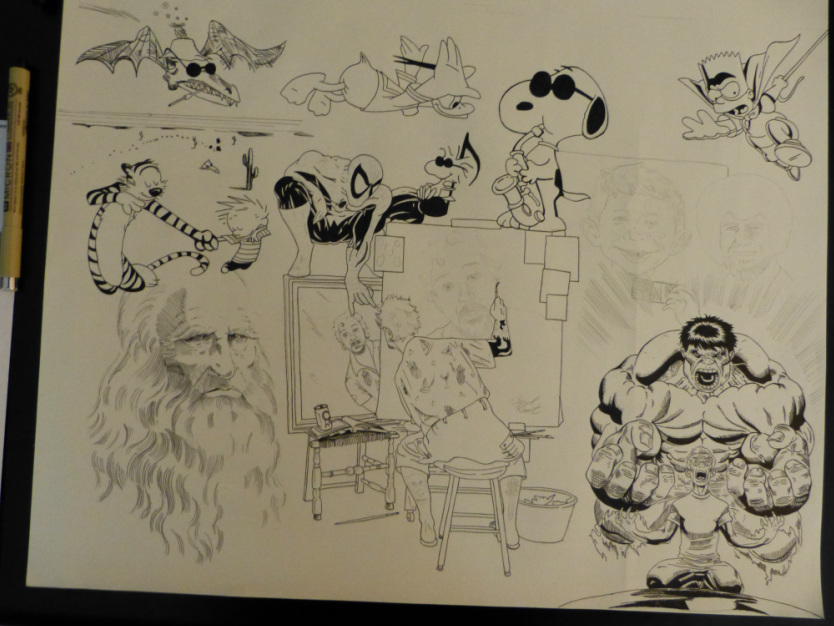

So, I sat down to do my best to illustrate this idea and the following is a sketch that I photographed just in case I screw it up with a brand of pen I’ve never worked with before (if Weebly is being honest with me, you should be able to click it for a larger view):

Currently, I’m considering it “A portrait of the artist as a young man hangin’ with that bad crowd”. I (originally) photographed it with the book “Steal Like an Artist” because all of those images are stolen and copied from some of my bad influences. That’s me in the middle of it all blatantly ripping off Norman Rockwell and taking his seat in his own “triple self-portrait”. Working on this image, and drinking too much coffee in the meantime, has made me reflect on this phenomenon of boundary maintenance in the arts. And the sciences.

Probably the same sort of thing occurs in music. It certainly seems prevalent in the social sciences. At the end of the day, I suppose I’m just folk as fuck. When I was a kid, I won a wooden plaque throwing darts into balloons at a local fair. It read: “Remember the Golden Rule: He who has the gold, makes the rules.” This was something I always felt and believed. Multiple experiences throughout my life confirmed this basic reality. So, it was probably natural for me to find solace in what is known in my field, or discipline, or whatever it is as “Critical Criminology”. My father once told me “don’t believe everything you read, or everything you see on TV.” This was far more influential in my developing a capacity for critical thinking and skepticism than, for example, Chomsky and Herman’s propaganda model.

Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not flipping the script here and getting all anti-intellectual. (Picture Adam Sandler’s “Waterboy” telling Colonel Sanders why alligators are so ornery…) But, as a qualitative researcher, I’ve been told and taught to be “reflexive”. To think about the beliefs, assumptions and so on that we bring to the table as social scientists. Well, I believe that my dad was a folk critical criminologist. And I believe that millions of people around the world are, too. If that means to question the taken-for-granted assumptions about crime and our response to it I’d say its rather naïve and foolish to think that we academics have some sort of monopoly on that particular skillset, even if we do have more access to the “body of knowledge”. Just like it is a little silly for the ivory tower gallery set to assume they get to define “art” for the rest of us.

Still, I’m supposed to have this thing “down to a science” by now, or at least by the time I walk away from USF with a doctorate in Criminology. But, what if I think it’s an art? Or philosophy?

Dammit. I was drawing to get away from this kind of thought.

Back to the drawing board.

Probably the same sort of thing occurs in music. It certainly seems prevalent in the social sciences. At the end of the day, I suppose I’m just folk as fuck. When I was a kid, I won a wooden plaque throwing darts into balloons at a local fair. It read: “Remember the Golden Rule: He who has the gold, makes the rules.” This was something I always felt and believed. Multiple experiences throughout my life confirmed this basic reality. So, it was probably natural for me to find solace in what is known in my field, or discipline, or whatever it is as “Critical Criminology”. My father once told me “don’t believe everything you read, or everything you see on TV.” This was far more influential in my developing a capacity for critical thinking and skepticism than, for example, Chomsky and Herman’s propaganda model.

Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not flipping the script here and getting all anti-intellectual. (Picture Adam Sandler’s “Waterboy” telling Colonel Sanders why alligators are so ornery…) But, as a qualitative researcher, I’ve been told and taught to be “reflexive”. To think about the beliefs, assumptions and so on that we bring to the table as social scientists. Well, I believe that my dad was a folk critical criminologist. And I believe that millions of people around the world are, too. If that means to question the taken-for-granted assumptions about crime and our response to it I’d say its rather naïve and foolish to think that we academics have some sort of monopoly on that particular skillset, even if we do have more access to the “body of knowledge”. Just like it is a little silly for the ivory tower gallery set to assume they get to define “art” for the rest of us.

Still, I’m supposed to have this thing “down to a science” by now, or at least by the time I walk away from USF with a doctorate in Criminology. But, what if I think it’s an art? Or philosophy?

Dammit. I was drawing to get away from this kind of thought.

Back to the drawing board.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed